Public Sample of the

Online Ministries Community Blog

|

Aug 08 |

How to Write for Web Pages - Part 7 - The Lead, a Learning Laboratory for Writing |

Posted by Bill Anderton

A purist would say that all of your writing is important. I take a more pragmatic view for people just beginning to develop their writing skills.

As I’ve written about elsewhere in this tutorial, you learn to write by practice, you write to learn to write. Many of you reading this tutorial will be rookies, writing for publication for the first time. The process of learning to write for your website is, in a very real sense, on-the-job training. You will be writing for your websites as you learn and improve your craft. Your first stories may not be very good. However, as you learn by doing, your second stories will be better and the third better still.

This on-the-job training of learning to write is classic even in newspapers.

Hopefully, if you are this far along in this tutorial, you are writing for your website. In the previous installments of this tutorial, we covered the high-level basics in of the writing and editorial process. My theory is that you should get started, even if you are a green rookie just learning to write.

With you now writing, it is time to circle back to focus on specific in-depth study about how to write. You will have a lot to learn, but there are some areas of study that will make your writing effective even early in your learning cycle.

In this installment of the tutorial, I will address the first in-depth study: how to write a lead.

In my humble option, you are well on the path to becoming a good writer of web pages if you can master the art of writing the lead. Leads form the foundation of every story. The lead is the first sentence or the first few paragraphs of a story. The lead gets your story going and draws the reader in and make them want to read more.

Leads are high-stakes writing. The lead is the most-important part of your story because its mission is to draw people into reading the rest of the story. You should learn to write good leads because you should! The sooner you learn to write good leads, the sooner your stories will be more effective.

I also believe that learning to write great leads is a great place to learn to become a better writer. First, writing better leads has an immediate payoff; they will make your stories better and draw more people into reading your web pages. Second, the small physical size of leads, typically less than 40 words, makes them perfect learning laboratories. With such a small piece of text, you can apply intense scrutiny to your text. You can easily invest the time and energies to craft your leads finely. However, everything that you learn while crafting your leads can also be applied to the rest of your writing.

Breaking a Bad Cycle

I can’t start teaching about how to write leads until we address an important precursor. You have to have something to write about, and you have to collect the information to have something with which to write.

In other words, you have to have the reporting!

I hope we are in agreement that there are lots of bad websites. Writing can improve them. However, a large part of the problem with poor church websites is the fact that there aren’t many stories on them. The problem isn’t just that there isn’t enough text on their pages; there is almost a total lack of reporting. In all of these bad websites, nobody is collecting the information of church activities in any meaningful way.

You might think that it will be tough writing great stories for many of the things you naturally will find in the life of the church. Most of these stories will be “small stories;” important, but still small in scope.

For example, the monthly meeting of the ladies’ auxiliary won’t happen in any dramatic way (usually) and it may not have an earth shattering impact on the price of oil. However, this is a totally inappropriate view. If the event was worthy of being staged, it is worthy of a good story on your website.

The ladies in the auxiliary thought it a worthwhile event, worthy of their time and effort doing it. You should honor that commitment by putting in the effort into writing a good story.

The root of the problem is within the cycle of collecting information in churches.

In the example of the ladies’ auxiliary meeting above, the typical cycle usually boils down someone from the auxiliary sending a brief note to the church secretary, who is typically the default reporter of the church. The note might include a time and place for the meeting and maybe a few other details. All of this information can fit on a 3” x 5” index card with room to spare.

The church secretary doesn’t have much to go on and doesn’t have the time to dig out any additional information. The church secretary works only with the information provided. The limited information provided gets added to the church calendar and maybe a short item in the church newsletter and Sunday bulletin. However, there the cycle stops.

For a church wanting a meaningful website, this is a bad cycle. You must break this cycle in order to move forward. Herein is where many of these types of stories and many church websites fail. Only the notice of the meeting gets posted, and nobody digs into the details. The lack of details means that any resulting story is thin gruel indeed, doomed from the beginning.

Writing good stories requires good reporting. A writer can’t write unless the write has the raw materials to write about.

Somebody has to do the basic reporting.

Somebody has to look deeper than just the fact that the auxiliary is meeting or has met. Somebody has to contact members of the ladies’ auxiliary and ask some basic questions. Why did they meet? What did they do in the meeting? What actions resulted? Who was there? Was there a featured speaker? Did they have lunch and, if so, what did they eat?

There are thousands of questions to ask, and someone has to ask them. This person is called a reporter. Reporters not only ask the questions but also figures out the right and best questions to ask.

With the questions asked and answered, the reporter has the raw material and can craft a story.

The story is within its details and reporting are required to find the details. You can’t gather too many details in the reporting phase. Some will be essential to the story other extraneous. A good reporter can tell the difference.

The quote is attributed to Michelangelo when asked about how he could sculpt such a magnificent statue of David. He reportedly replied, “It’s simple. I just remove everything that doesn’t look like David.”

A writer does this same type of carving with all of the details collected in reporting. With all of the details collected, the writer eliminates some that are extraneous and prioritizes the remainder. Somewhere in the pile of facts on their desks is a great story waiting to get out.

Good leads come out of good reporting. Writing the lead is simply a matter of removing everything that is non-essential and presenting the remainder to the reader in the most-readable way.

What is a Lead?

The lead of the story is the first part of your story, the first sentences or its opening paragraph.

All leads for stories should meet basic two requirements.

- It should capture the essence of the story

- It should compel the reader to read more.

The two operative words are capture and compel.

For example, even the weather forecast, never know to be a haven of good writers, can be enhanced with a strong lead. H. Allen Smith of New York World‑Telegram, proved the point when he wrote:

“Snow, followed by small boys on sleds.”

Or, a lead can be shocking and deliver a punch in the gut. For example, St. Clair McKelway, of the Washington Herald, in a story about a disabled World War I veteran living in poverty:

“What price Glory? Two eyes, two legs, an arm and $12 a month.”

Both of these leads are great! Both capture the essence of their respective stories and compel you to want to read more.

A great lead grabs you by the lapels and shakes you while commanding, “Read me!” What is remarkable is that leads can do these two important things in so few words. Brevity is part of the art of writing leads is that they can do so much with a few simple words; seven words in the first example and 13 words in the second.

Great Beginnings

The mission of the lead is to grab your readers’ attention from the start. A good lead compels the reader to read more. A good lead sets the tone of the article and telegraphs its direction. It is like advice your mother would give you, “Make a good first impression.”

One cannot write about leads without using the Bible as a prime example. The Old Testament starts with a short sentence that uses simple words in a single short sentence:

"In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth."

In English, this lead is just ten simple words, yet everyone remembers it. I don’t think it is too much of a stretch to say a significant percentage of the people on the planet know this most-famous of all leads.

Writing good leads is a case of getting off to a good start with your readers. The lead is the most-important text in your story. It should be concise and clear. It should also be interesting.

However, there is no avoiding the fact that writing leads are hard work. Developing great lead is well worth the effort, but it isn’t easy.

Jack Cappon of The Associated Press hit the nail on the head, writing:

“The agony of square one.”

There is no getting around it, although every writer sometimes wishes there were. Every story must have a beginning. A lead. Incubating a lead is a cause of great agony. Why is no mystery. Based on the lead, a reader makes a critical decision: Shall I go on?”

On point, Mitch Albom, Detroit Free Press writes:

“I look at leads as my one frail opportunity to grab the reader. If I don’t grab them at the start, I can’t count on grabbing them in the middle because they’ll never get to the middle. Maybe 30 years ago, I would give it a slow boil. Now, it’s got to be microwaved.

I don’t look at my leads as a chance to show off my flowery writing. My leads are there to get you in and to keep you hooked to the story so that you can’t go away.”

Also, Don Wycliff of the Chicago Tribune says:

“I search for a lead. I guess I’ve always been a believer that if I’ve got two hours in which to do something, the best investment I can make is to spend the first hour and 45 minutes of it getting a good lead, because after that everything will come easily.”

Examples of Great Leads

To understand what leads are, you have to be exposed to some good ones. It is one thing to have an academic understanding of the definition of a lead. It is quite another to see the power of great leads in action in real-world examples.

To best understand leads, you need to see some good ones. Therefore, we’re going to take some time here to show you some great examples.

First, examples of great lead can be found in great literature.

Charles Dickens’ The Tale of Two Cities:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

I am showing the whole lead in this example but could have stopped after, ““It was the best of times, it was the worst of times …” How could one not read the whole book after reading its lead?

Herman Melville’s Moby Dick:

"Call me Ishmael."

The three-word sentence is, arguably, the most-recognizable lead in Western literature and my personal favorite.

Now, just to show modern literature can write great leads too, I can offer two more examples.

Curtis, Christopher Paul Curtis’ The Watsons Go to Birmingham

“It was one of those super-duper-cold Saturdays. One of those days that when you breathed out your breath kind of hung frozen in the air like a hunk of smoke and you could walk along and look exactly like a train blowing out big, fat, white puffs of smoke. It was so cold that if you were stupid enough to go outside your eyes would automatically blink a thousand times all by themselves, probably so the juice inside of them wouldn't freeze up. It was so cold that if you spit, the slob would be an ice cube before it hit the ground. It was about a zillion degrees below zero.”

Avi’s The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle:

"Not every thirteen-year-old girl is accused of murder, brought to trial, and found guilty. But I was just such a girl, and my story is worth relating even if it did happen years ago."

All of the above examples were from fiction where writers can make up their leads from whole cloth. I am deliberately using these leads as an opening example to get you to understand what a lead is and how effective a good one can be at capturing your attention even at the beginning of a significant work of literature.

However, news and reportage are not-fiction (hopefully), and writers not only have to write good leads, but also convey the facts from the story, the essential core truth of the item. Writing non-fiction leads is a bit harder to do because the writer has to work with the scope of the facts of the story. Even still, news of actual events can yield leads that are also good literature that just happens to be true and covers the meat of the story in the first paragraph.

I have to start my news examples with a classic. In 1924, Grantland Rice, the legendary a sportswriter for the old New York Herald Tribune, wrote, "the most-famous football lead of all-time" about Notre Dame's 13–7 upset victory over Army:

“Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore their names are Death, Destruction, Pestilence, and Famine. But those are aliases. Their real names are: Stuhldreher, Crowley, Miller and Layden. They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds this afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down upon the bewildering panorama spread out upon the green plain below.”

Over the last 90 years, this lead has become a caricature of itself as thousands of lesser writers have all but plagiarized it, complete with Rice’s proclivity for apocalyptic apotheosis. Most, lacking Rice’s skill, fall flat and produce leads that are almost parody and usually pretentious.

Just to show that great leads aren’t always in highfalutin language, Blackie Sherrod, equally legendary sports columnist of the Dallas Times-Herald in 1960, wrote of the 1960 Harvard vs. Yale football game:

“As long as he’s in the vicinity, don’t you know, a chap should certainly take in The Game. And iffen you don’t know what The Game is, then you ain’t got a large amount of couth and don’t stand there wiping your nose on your sleeve and mumbling apologies.”

Yep, he actually used “iffen” in a sentence. Often littered in Blackie’s Scattershooting columns were quirky use of words to add flavor. He loved the English language and certainly had a master’s command of it. But, Blackie had a lesson in his writing: don’t be too full of yourself when you write.

Straightforward sentence construction didn’t mean that writing couldn’t be elegant. One of my favorite Blackie Sherrod leads, writing about a heavyweight contender:

"He has everything a boxer needs except speed, stamina, a punch, and ability to take punishment. In other words, he owns a pair of shorts."

As a sidebar, Blackie was a legend and was called, “The best that is, was and ... ever will be.” The writers that he assembled in the 1950s for his sports department that he edited at the old Ft. Worth Press (where I did my journalism internship in 1969) was perhaps the best ever assembled at a daily: Bud Shrake, Andy Anderson, Jerre Todd, Gary Cartwright and Dan Jenkins.

To make Blackie’s point by contrast, and use another Grantland example, Rice also wrote of another Harvard vs. Yale game in 1923:

“On a gridiron of 17 lakes, five quagmires and eight water hazards, Yale rode through the surf of a tidal wave to beat Harvard by 13 to 0 this afternoon, in the strangest football ever played. Under conditions that would have baffled Johnny Weismuller and a shoal of fish, the Blue came back to glory above the beaten Crimson for the first time in seven years. And for the first time in 14 long and weary years a Yale team cut its way to victory upon a Harvard field, rising above destiny itself to reach the heights.”

Now, you should contrast Rice’s lead with Sherrod’s. Two great leads but very different.

Roy Peter Clark, in his 2006 blog post, “Passing the Torch: Don’t Let Great Sportswriting Flame Out” provided an analysis the 1923 Rice lead:

“OK, so it’s a little inflated, but the New York Tribune could tolerate 100-word leads back then. A thriftier scribe might have written: “Finally, Yale beat Harvard 13 to 0 — on the road and in the rain.”

Clark does make an excellent point that is at the heart of good leads: economy of language is a good thing.

In the Grantland Rice style, it is always a temptation to put art of crafting the language of a lead too far ahead of reporting the news; all too often, slightly ahead of the facts too. Unless you have Grantland Rice’s skills, it is easy to cross in the line and fall into the caricature version.

Sticking to clear and concise straight-news style of writing leads much preferred, particularly while you’re learning the craft.

Great News Leads

Much of what you will write will be news leads. You will have stories to write on events and happenings, the things that go on in the life and ministry of your church. These are things that fit my definition of news.

Each will require a lead. To provide some specific examples of news lead, I will now show you some great lead; all published in US daily newspapers.

News leads are important, so the American Society of News Editors has a category for leads in its national award program. Here is a sample of ASNE award-winning leads from the recent past.

Note the simplicity of each’s construction but each’s powerful use of the language and ability to engage you. You should also note how each headline paired with each lead.

“Terror Rides a School Bus” by Gail Epstein, Frances Robles and Martin Merzer, The Miami Herald:

“A waiter fond of poet Ralph Waldo Emerson attends morning prayers at his church, steps across the street and hijacks a school bus. Owing $15,639.39 in back taxes, wielding what he says is a bomb, Catalino Sang shields himself with disabled children.

Follow my orders, he says, or I will kill the kids. “No problem, I will,” says driver Alicia Chapman, crafty and calm. “But please don’t hurt the children.”

The saga of Dade County school bus No. CX-17, bound for Blue Lakes Elementary, begins.”

“A summons from history” by Susan Trausch, The Boston Globe:

“The past came to claim Aleksandras Lileikis this week. It knocked on his door on Sumner Street in Norwood, shattering his quiet present and shocking the friends and neighbors who thought they knew the man in the yellow house. It knocked on all of our doors, pointing to the genocide of more than 50 years, demanding that we hear the stories and seek the truth.”

“Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin is Killed” by Barton Gellman, The Washington Post:

“JERUSALEM, Nov. 4—A right-wing Jewish extremist shot and killed Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin tonight as he departed a peace rally attended by more than 100,000 in Tel Aviv, throwing Israel’s government and the Middle East peace process into turmoil.”

“A murder story” by David Finkel, St. Petersburg Times:

“Her weight’s gone up. Gray hairs have sprouted. She’s gotten used to flat shoes instead of heels and eggplant-shaped dresses instead of the gowns and furs she used to wear. But after a decade in prison for having her husband killed, Betty Lou Haber, closing in on 50, is still as polite and sweet sounding as ever.

“There’s never a night that I go to bed and don’t say my prayers,” she said last week. “I just do the best I can.”

And that’s why Albert Haber’s surviving children are worried.”

“A sentimental journey to la casa of childhood” by Mirta Ojito, The New York Times:

“HAVANA—This is the moment when, in my dreams, I begin to cry. And yet, I’m strangely calm as I go up the stairs to the apartment of my childhood in Santos Suarez, the only place that, after all these years, I still refer to as la casa, home.”

“Only Human Wreckage Is Left in Karubamba” by Mark Fritz, Associated Press:

“Karubamba, Rwanda—Nobody lives here anymore.

Not the expectant mothers huddled outside the maternity clinic, not the families squeezed into the church, not the man who lies rotting in a schoolroom beneath a chalkboard map of Africa.

Everybody here is dead. Karubamba is a vision from hell, a flesh-and-bone junkyard of human wreckage, an obscene slaughterhouse that has fallen silent save for the roaring buzz of flies the size of honeybees.”

“It Fluttered and Became Bruce Murray’s Heart.” By Jonathan Bor, Syracuse Post-Standard:

“A healthy 17-year-old heart pumped the gift of life through 34-year-old Bruce Murray Friday, following a four-hour transplant operation that doctors said went without a hitch.”

“After Life of Violence Harris Goes Peacefully” by Sam Stanton, The Sacramento Bee:

“SAN QUENTIN—In the end, Robert Alton Harris seemed determined to go peacefully, a trait that had eluded him in the 39 violent and abusive years he spent on earth.”

“Facing the void of a life and a love lost in a moment” by Joan Beck, Chicago Tribune:

“At 12:30, my husband and I were having a pleasant lunch in a restaurant. At 1:30, we were back home, sitting at the kitchen counter planning a trip to Vienna and Budapest with cherished friends. At 2:30, I was walking out of the hospital emergency room in shock, a widow, my life changed forever, beyond comprehension.”

“Tattoos and freedom” by Michael Gartner, The (Ames, Iowa) Daily Tribune:

“Let’s talk about tattoos.”

“Tornado sneaks into Manila, killing 2 kids just as sirens wail” by Bartholomew Sullivan, The (Memphis) Commercial Appeal:

“MANILA, Ark. - It killed first, then it came into town.”

“The ‘good book’ on prime time” by Dorothy Rabinowitz, The Wall Street Journal:

“Hide the school-age children and call out the American Civil Liberties Union and the People for the American Way. The Bible is coming to television, right out in public where everyone can see and hear it__or, anyway, that version of it to be aired on Arts & Entertainment for four nights beginning Sunday (8-9 p.m., EST).”

“Small town grieves 21 dead” by Ken Moritsugu, Newsday:

“MOUNTOURSVILLE, Pa. They knew them as the girl who spilled the fries in the car. Knew them as the boy who shot baskets and lighted the candles at church. Knew them as the girl who wrote poetry and played the piano.”

“A few Coors Lights might blur the truth” by Steve Lopez, Los Angeles Times:

“It was about 8:45 Thursday morning when I walked into the Hermosa Beach Police Department with two dozen Krispy Kreme doughnuts and a 12-pack of Coors Light.”

Bad vs. Good Lead

Now that you have seen a lot of great leads, I’ll contrast a bad lead with a good lead.

Bad lead:

“On Saturday, March 1, 2014, three students won a regional choral competition.”

Good lead:

“Three Highland Park juniors took home $500 and top honors Saturday in the SMU regional choral contest.”

Note that the bad lead provided too little information while, at the same time extraneous information, specifically, the full date.

I hope you can see how bad the first lead is for the purpose of learning how to write a good lead.

Finding the Lead

You can’t always just sit down and write a great lead. There is a process.

Before one can find the words to put into the lead, the writer has to sort out the facts of the story; sift through the facts to find the central focus of the story. This sifting of the facts begins long before the writer types the first charters of the lead.

We can start with asking ourselves two important questions:

- What was truly unique or what was the most important or unusual thing that happened?

- Who was involved; who did it or who said it?

These two questions try to drill straight to the heart of the matter. The answers form the essence of your emerging lead and establish the overall scope of the lead.

Now, the writer needs for put some flesh on the skeleton by looking for words to use in the lead that provide shape, form and color. A writer can try to find these words by asking three more questions:

- Is it best to use direct or delayed lead?

The direct lead puts the theme of the story in the first sentence of the lead. It goes directly to the point. It is very easy to read and succinct. Typically, it uses straight subject-verb-object construction. breaking news events use direct leads.

Often used in feature stories rather than fast-breaking events, the delayed lead usually sets the scene of the story or evokes its mood with an anecdote or example. In the delayed lead, the theme goes somewhere within the first several paragraphs of the story.

- Is there a colorful or dramatic word or phrase that fits the situation?

Even when describing the same thing, certain words are better than other because they bring color, drama or gravitas. Your lead can only be a few words so select each with care.

- In the sentence structure, what are the subject, and what verb will engage the reader and interest them in the story?

Many leads use a straightforward subject-verb-object structure. The lead should start with the subject, closely followed by an active verb and conclude with the object of the verb. Finding the right subject noun and action verb is very important in the success of the lead. Many times rookie writers put too much energy into flowery adjectives and adverbs when the time would be better-spent in the nouns and verbs.

Yes, all of this is very subjective and creative. Being subjective, and creative doesn’t mean you have the fiction author’s license to make things up; you still must deal with the essential truth of the matter. However, you are trying to cut away all of the extraneous things that get in the way of seeing the truth, getting past the spin and sometimes downright obfuscation.

From writer John McPhee”

"The first part‑the lead, the beginning‑is the hardest part of all to write. I've often heard writers say that if you have written your lead you have 90 percent of the story. Locating the lead is a struggle.”

Good Reporting Makes Good Leads

Simply put, you can’t write a good lead with doing good reporting first. If you don’t do the field work, you won’t know the story. You won’t now the details. You won’t have a first-hand feel of the theme of the story.

Weak leads can be the direct result of inadequate field reporting. Consider this example of a weak lead:

“Jane Elizabeth Doe, member of the Sojourners Class, will be Chair of the church bazaar.”

The reporter failed to provide any single interesting characteristic of the new Chair other than her membership in the Sojourners Class. Surely, more could be learned.

Omitted were interesting characteristics that could be added to the story because the writer didn’t pick up the phone and call Jane Elizabeth Doe.

If so, even a two-minute call might yield:

“Jane Doe, following in the tradition her mother and grandmother, will become the third Doe to serve as Chair of the church bazaar.”

Or, with more reporting:

“New Chair will bring the Church bazaar into the Internet era with an online auction.”

The more you learn about your story, the easier it becomes to find a lead.

SVO Construction

With the lead found but not yet written, start thinking about how you are going to write and the sentence construction you will use.

Subject-verb-object (SVO) construction is a classical structure of a sentence construction for news writing. The subject comes first in SVO construction, the verb second, and the object third. SVO construction typically places relative clauses after the nouns they modify and adverbial subordinators that go before the clause modified.

SVO construction is the meat and potatoes of journalistic writing.

SVO construction contains an internal imperative: it commands the writer to write simple sentences with one main clause. This kind of construction inherently keeps leads short that is a major requirement for making the lead readable.

For example, here is a direct lead of a basic new story:

“Federal Judge Barefoot Sanders has ordered the Dallas Independent School District to submit a new segregation plan by the 1982-83 school year.”

Where:

- S = “Barefoot Sanders”;

- V = “has ordered”;

- O = “Dallas Independent School District."

The majority of direct leads use the SVO construction. It parallels the basic pattern of speech and fits a basic journalism rule-of-thumb, "Write as you talk." It is the shortest, most-direct way of answering the first two questions all reporters asks “What” and Who.” What happened? Who was involved?

The SVO construction does permit a variety of writing styles. For example, below are the leads that were written the night of the Sonny Liston vs. Floyd Patterson heavyweight championship fight on September 25, 1962, in Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois:

UPI:

“BULLETIN

CHICAGO, Sept. 25 (UPI) SONNY LISTON KNOCKED OUT FLOYD PATTERSON IN THE FIRST ROUND TONIGHT TO WIN THE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP OF THE WORLD.”

Robert L. Teague, The New York Times

“CHICAGO, Sept. 25 ‑ Nobody got his money's worth at Comiskey Park tonight except Sonny Liston. He knocked out Floyd Patterson in two minutes, six seconds of the first round of their heavyweight title fight and took the first big step toward becoming a millionaire.”

Jesse Abramson, The Herald Tribune

“CHICAGO, Sept. 25 ‑ Sonny Liston needed all of two years to lure Floyd Patterson into the ring and only two minutes, six seconds to get him out of it in a sudden one‑knockdown, one‑round‑knockout at Comiskey Park last night.”

Leonard Lewin, The Daily Mirror

“CHICAGO, Sept. 25 ‑ Floyd Patterson opened and closed in one tonight. It took Sonny Liston only 2:06 to smash the imported china in the champ's jaw and, thereby, record the third swiftest kayo in a heavyweight title match ‑ a sudden ending that had the stunned Comiskey Park fans wondering wha' hoppened. The knockout punch was there for everyone to see. It was a ponderous hook on Patterson's jaw. But the real mystery was what hurt the champ just before that; how come he suddenly looked in trouble when Liston stepped away from a clinch near the ropes?”

Gene Ward, Daily News

“CHICAGO, Sept. 25 ‑ It was short, sweet and all Sonny Liston here tonight. The hulking slugger with the vicious punch to match his personality teed off on Floyd Patterson, knocked the champion down and out at 2:06 of the first round and won the world heavyweight championship without raising a bead of sweat on his malevolent countenance.”

Note that all the reporters agreed on the news angle, Liston's quick KO of Patterson.

- S = “Liston”;

- V = “knocked out”;

- O = “Patterson”.

As a newswire service, the UPI lead had to go out first. Newswire services and their reporters are under incredible time pressures. Seconds count! Their lead moved over their wire within seconds of the referee counting out Patterson. With no time available to them, they had to craft a straight SVO lead.

However, all of the reporters’ questions were answered in this short lead of 23 words:

- Who – “SONNY LISTON” and “FLOYD PATTERSON”

- What – “HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP OF THE WORLD”

- Where – “CHICAGO”

- When – “Sept. 25” and “IN THE FIRST ROUND”

- Why – “TO WIN”

- How – “KNOCKED OUT”

The other four reporters in the example all worked for New York City morning dailies. At the end of the fight, their deadlines were hours away. Not under the same deadline pressure, they had time to craft their leads.

Readability of Leads

The mission of leads implies their readability. One lead that is more readable and another is better.

Simple enough, but how do you improve the readability of your leads?

The readability of a lead results from three things:

- The ideas that makeup each sentence in the lead – Each sentence in the lead should contain one idea when possible. Realize too, that many leads are just a single sentence. Sir Herbert Read, in English Prose Style, says, "The sentence is a single cry." If you put too many ideas in a sentence, you make reading more difficult to get through. Each idea selected for each sentence should be easy quickly to understand. Simply any complexities in the idea so clearly expressed.

- The order in which words appear in sentences - The subject‑verb‑object construction is the most often used because it is the easiest to understand.

- The words and phrases the writer uses to give the ideas expression – The lead hinges on its subject and verb. Therefore, the choice of nouns and verbs is a big part of readability. The subject should be a noun that the reader implies sensory experiences like hearing, seeing, tasting, feeling or smelling. The noun should stand for a name or thing. The verb selected should be a colorful action verb that moves the reader to the object. Alternately, the verb could make the reader pause and think. The choice between a transitive (allows an object), and intransitive verb (does not allow an object) is important.

Testing Your Lead

The Five W’s and H that we discussed earlier in this tutorial can help: who, what, when, where, why and how. These basics will help you get to the truth in the first of your lead.

You should work in the most-important answers near the beginning of your lead. Less important aspects can wait until further down in the lead, the second- or third sentence.

Not all six of these questions will be relevant in all cases. However, they provide a good test. First, write your lead. Then, check how many of the six questions are answered. If you missed some, there should be two possible reasons with two possible outcomes:

- The question isn’t relevant - do nothing, skip it.

- The question is relevant - rewrite your lead.

Lead Length

There is always a creative tension between wanting to write longer leads to provide more information and shorter leads that are more readable. The long lead may be difficult to grasp; the short lead may be uninformative or misleading.

Leads should be 35‑words or less if possible.

The Associated Press teaches its reporters that “when a lead moves beyond 20‑25 words it's time to start trimming."

Edit some of the extra verbiage such as:

- Unnecessary attribution.

- Compound sentences joined by “but” and “and”

- Exact dates and times unless essential

Some leads will require full information in the lead, and if the rhythm and balance are right, the long lead can be used.

Types of Leads

There are a lot of different ways to write a lead; each in a different style. Categorizing different approaches to writing leads into lists can be helpful when studying leads.

However, this should be an academic exercise. I’m not suggesting that the list below should necessarily be used to pick a lead for your story.

Instead, let the essence of your story determine the lead.

The list below will show you only some options you can use when writing your lead.

- Direct lead - Perhaps the most-traditional lead used in news, often used for breaking news. It moves directly to the point and is succinct and readable.

- Summary lead - Summary leads to provide answers to the most important three or four of the Five W’s and H questions, usually the who, what, when and where. Write Summary leads as straight SVO construction.

- Single-item lead – The Single-item lead focuses on just one or two question elements of a Summary lead for a bigger impact.

- Delayed identification lead – The Delayed identification is also like a Summary lead, but withholds clearly identify the subject (the who question) right away.

- Contrast lead - The contrast lead … well … contrast! The more polar the two opposite extremes, the better: happy with sad, rich with poor, youth with age, past with the present.

- Opposite lead – The Opposite lead is a variation of the Contrast lead that first provides first one point of view and then follows with the opposing view.

- Analogy lead – The Analogy lead is similar to the contrast lead but comparison between two things, one of which being familiar to the average reader. This lead helps when you have a complex topic to explain to laymen.

- Picture lead - The picture lead paints a word picture of the subject of the story. The more detailed your word picture is, the better the lead will work.

- Background lead – The background lead is similar to the Picture lead but paints the word picture or the story’s surroundings, background or circumstances.

- Scenic lead - The scenic lead paints a word picture of the scene surrounding an event. Use the scenic lead where the setting is a prominent part of the story, such as festive events, performances and sports. It is also used where the mood of the scene is appropriate for the story.

- Punch lead - The Punch lead is a jolting, in-your-face statement that is blunt and explosive. The objective is to surprise or perhaps shock the reader.

- Amazing fact lead – The Amazing fact lead put some amazing fact in the first sentence of the lead that arouses readers’ interest

- Anecdotal lead – One tried-and-true method is leading with a short on-point anecdote. A key aspect of using this type of lead successfully requires the story having an anecdote that can be interesting and match the story’s theme. The details are necessary, and the broader significance of the anecdote should be obvious and explained within just a few sentences.

- Question lead – As its name implies, the Question lead asks a pertinent question. The objective is to make the readers curious and want to read more of the story to find the answer. The question should be rhetorical, and not answered simply.

- Direct address lead – This lead is like talking directly to the readers. It either uses the “you” and “your” pronouns or directly implies them. The objective is to make the readers collaborators in the story.

- Quotation lead – The Quotation lead features direct quote from a principal actor within a short. The quote is almost always, expressed within quotation marks. The quote has to be short and pithy. It should be remarkable and eye-catching.

- Short sentence lead – The short sentence lead uses one word or a very short phrase as a teaser. Obviously, the words used should engage the interest of the reader for the remainder of the lead. This type of lead can be gimmicky, so use it with caution and sparingly.

- Wordplay lead – The Wordplay lead uses a clever turn of phrase, be it a name or word. The Wordplay lead must be used equally cleverly because it can mislead the reader. If your lead causes readers to think your story is about one thing only to find out it’s about another, they will get annoyed.

- Storytelling lead – The Storytelling lead uses a strong narrative style. It begins by introducing the main characters of the story, the conflict, and perhaps the setting of the story. The objective of this lead is to make readers feel drama and become curious about what's going to happen next.

- List lead – The List lead impresses the reader with long list things rather than focusing on one person, place or thing.

- Rule breakers lead – The rule breaking lead defies most of the commonly-accepted canon of journalistic writing. They might employ clichés, questionable taste reporter anonymity. However, they work because they are impeccably memorable, represent the theme of the story and compel the reader to read on.

Don’t Bury the Lead

“Don’t bury the lead” is surely carved in granite somewhere, writ by the hand of Moses. It is a commandment. It is also wise advice.

Burying the lead is putting information of secondary importance ahead of the true lead which has the information of primary important. Often leads are buried several paragraphs into the story.

Burying the lead can postpone engaging the reader causing the reader to have to wade through extraneous or less important details before they get to the good stuff. The problem is that some readers won’t dig this deep into your story with a buried lead; you will lose them in the less important details. Your buried lead will fail to engage.

Burying the lead often results from poor writing technique but it can also result when the writer doesn’t fully grasp the essence of the story. In these cases, the writer fails to find a lead.

The failure to understand the importance of key elements of the story is what truly frightens most-professional journalists and why they often agonize over the lead.

Don’t Write Writing

Melvin Mencher, professor emeritus at the Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University says:

“Immersed in words, the reporter is tempted to write writing, to make meaning secondary to language. This is fine when a poet plays with words, but it is dangerous for a journalist, whose first allegiance is to straightforward expression. Word play can lead to tasteless flippancies.

Good journalism is the accurate communication of an event to a reader, viewer or listener. As Wendell Johnson, a professor of psychology and speech pathology at the University of Iowa, put it, "Communication is writing about something for someone making highly reliable maps of the terrain of experience." Johnson would caution his students, "You cannot write writing."

The reporter who puts writing before fact gathering will achieve notoriety of a sort, if he or she is clever enough. Such fame is fleeting, though. Editors and the public eventually flush out the reporter whose competence is all scintillation.

This is not a red light to good writing. In fact, the fashioning of well--written stories is our next objective.”

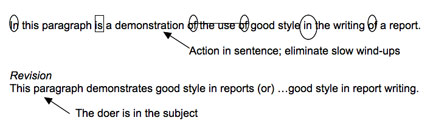

Paramedic Method: A Lesson in Writing Concisely

Writing concise leads are important for their effectiveness. They should be clean and crisp.

Richard Lanham in Revising Prose developed a method for editing prose called Paramedic Method. It is easy to learn and apply to editing and polishing your leads.

The Paramedic Method:

- Circle the prepositions (of, in, about, for, onto, into)

- Draw a box around the "is" verb forms

- Ask, "Where's the action?"

- Change the "action" into a simple verb

- Move the doer into the subject (Who's kicking whom)

- Eliminate any unnecessary slow wind-ups

- Eliminate any redundancies.

Try the Twitter Test

After you have honed your lead, try tweeting your lead on Twitter, the social network. Tweets are limited to 140 characters that are about 20-22 word. If lead doesn’t work, it might be too long, or it might not be strong enough to stand alone.

You can only imagine how it works if you don’t want to make it public too soon. However, tweeting you lead to get feedback isn’t a bad idea.

Tips for Writing a Lead

- Keep it simple. Often writers try to tell too much in their leads. You should boil things down to their essence.

- Though you are summarizing information in most leads and into very few words, try to be specific as possible. If you lead too broad, it won’t be informative or interesting.

- Many great stories have conflict. So can good leads.

- Watch your punctuation. The best lead only has a period in a sentence. Consider multiple commas or dashes or other pieces of punctuation should as red flags.

- Read your lead aloud, Read aloud, you can hear whatever might not flow smoothly or is choppy.

- Brevity counts. It is natural that readers want to know if the story matters to them. Also, they want to find out as fast as possible, immediately. They won’t wait or dig for the answer. Leads are often one sentence, maybe two. They should be 25 to 30 words and rarely be more than 40. These word limits are somewhat arbitrary, but brevity is the general idea.

- Challenge, challenge, challenge. Challenge prepositions and conjunctions used in your lead. Are they worth the words? Challenge your adjectives and adverbs. Would the lead be stronger without each? Could a more specific verb or stronger noun eliminate the need? Challenge any phrases. Will the elimination of the phrase help the lead? Can a single word replace a phrase?

- Only use active sentences with strong verbs to make your lead lively and interesting. Passive sentences can sound dull and leave out important information. Inadequate reporting can be the reason for passive leads.

- Know your audience and the context for your story. Consider what your reader already knows.

- Minimize attribution. More to the point, eliminate the need for attribution. Can you state something as a fact? Attribution not only lengthens a lead, it weakens it. If you didn't something as a fact, it might mean you don’t have the right reporting to be writing more authoritatively?

- Put a high value on honesty. Your lead is a contract with your readers. Stories must deliver what their lead promises in order to retain readers’ trust

- Flowery language is a no-no. Rookie writers often overuse adverbs and adjectives in their leads; this is a mistake. Instead, concentrate on the strength of the verbs and nouns you use.

- Avoid hedging words like “hope” and “look to” in leads. A hedge is a hedge and is inherently weak.

- Watch out for unnecessary words or phrases. Check for unintentional redundancies. You can’t waste the space for extra or unneeded words in your leads. Cut all of the clutter. Good directly to the heart of the story.

- Avoid using lengthy introductory clauses in your lead. If your lead requires it, rewrite your lead.

- Always avoid formulaic leads. Deadline pressure and writers’ block can make the temptation to turn out tired, formulaic leads strong.

- Don’t use clichés.

- Readers not only want information, but they also want to be entertained as they get it. Your lead must always sound genuine, not merely mechanical.

- Don’t start a lead with the word “It.” Editors frown on it because it is imprecise.

Things to Avoid

- Flowery language is a no-no. Rookie writers often overuse adverbs and adjectives in their leads; this is a mistake. Instead, concentrate on the strength of the verbs and nouns you use.

- Avoid hedging words like “hope” and “look to” in leads. A hedge is a hedge and is inherently weak.

- Watch out for unnecessary words or phrases. Check for unintentional redundancies. You can’t waste the space for extra or unneeded words in your leads. Cut all of the clutter. Good directly to the heart of the story.

- Avoid using lengthy introductory clauses in your lead. If your lead requires it, rewrite your lead.

- Always avoid formulaic leads. Deadline pressure and writers’ block can make the temptation to turn out tired, formulaic leads strong.

- Don’t use clichés.

- Readers not only want information, but they also want to be entertained as they get it. Your lead must always sound genuine, not merely mechanical.

- Don’t start a lead with the word “It.” Editors frown on it because it is imprecise.

Leads Checklist

Appalachian State University website has published a good check for leads at http://studentmedia.appstate.edu/leads:

"Use this checklist to write, evaluate, and improve your story leads.

- ENTICE Does your lead entice the reader to read on?

- FOCUS Is your lead going to take the story in the direction you want it to go?

- FORESHADOW Does the lead foreshadow something which will come later in the story? Are the details you chose meaningful to the story? If you have used an anecdotal lead, does it illustrate an important point in the story? In other words, do you have backup for the lead?

- GRAB Is the lead a grabber? Does it cause readers at the breakfast table to spit up their coffee, clutch at their heart and shout, “Good grief! Honey, did you read this?” Maybe the readers won’t spit up their coffee, but your lead should definitely arouse their interest.

- PROMISE Does your lead follow the “tell it to a friend” theory? Does it promise a good story?

- SO WHAT? Can your lead pass the “who cares” test? Can you answer the question, “Why should someone read this?

- VIEW Have you selected a point of view in the lead appropriate for the story (first, second, or third person point of view) and is your text consistent with that point of view throughout your lead?

- VOICE Does the lead convey a voice for the story- mysterious, dramatic, sympathetic, sarcastic, poignant, angry, sad, amused, humorous, caring, or any other emotion? Make sure the voice merely sets the tone and does not project your opinion—only your observations of the subject you are writing about.

- MEMORY What is the most memorable detail, fact, or impression you discovered during your interviews for the story? Is that in your lead? If not, should it be?

- RHYTHM When you read your lead aloud, does it have rhythm? Does it flow well and sound interesting to you?"

Summing Up

Good leads with the writer gaining a clear understanding of the theme of the story. Understanding comes through complete reporting and everything else follows:

- Find all of the essential elements of the story.

- Decide whether direct or delayed lead better suits the story.

- If only one essential element stands out, use a single‑element lead. If more than one, use a multiple‑element lead.

- Use the SVO sentence construction.

- Use concrete nouns and colorful action verbs.

- Always keep your lead short, under 30- or 35 words and don’t go over 40.

- Always make your lead readable, but do not sacrifice accurate reporting for readability.

Category: (08-14) August 2014 Tag:

This is only the blog's abstract. To read the full text and participate in all of the interactive features of the community, please register. It's FREE!

Click Here To Register Into This FREE Community